ÁRIDO

O SANGUEDERRAMADO

the

names

of

countless

victims

killed

cleansed

hidden

separated

objetified

destroyed

shanked

shot

tortured

hanged

stomped

raped

cut

beaten

gunned down

exploded

cooked

burned

drowned

waterboarded

gassed

crushed

experimented on

disintegrated

sliced

destroyed

shanked

shot

tortured

hanged

stomped

raped

cut

beaten

gunned down

exploded

fucked

shot

splited

divided

conquered

colonized

humiliated

Huremović Sabrija Graho Huremović Safet OmerHuremović Samir MešanHuremović Ševal Fahrudin

Huremović Ševko MustafaHuremović Teufik Nurija Huremović Velid Alija

Huremović Zenudin Nurija Hurić Edin Adem Hurić Ibran IbroHurić Ibro Adem Hurić Meho Hamza

Hurić Mevludin Ibran

Hurić Muhidin Nurija

Hurić Mujo Nurija

Hurić Omer Bajro Jašarević Ahmet Halid Jašarević Ahmet Ismet

Jašarević Asim Fejzo Jašarević Avdo Adem

Jašarević Avdo Avdija Jašarević Bajro Osman Jašarević Bekir Alija

Jašarević Damir Džemil Jašarević Džemil Salko Jašarević Esad Alija

Jašarević Fikret Mujčin

Jašarević Fikret Rašid

Jašarević Halil Mujo Jašarević Hamid Salko

Jašarević Hazim Salih

Jašarević Husein Ibro

Abdurahmanović Hajrudin Šefko

Abdurahmanović Idriz Fehim

Abdurahmanović Ismet Nezir

Abdurahmanović Mehmed Nezir

Abdurahmanović Mehmedalija Juso

Abdurahmanović Nisad Ismet

Abdurahmanović Sakib Idriz

Abidović Fikret Ferid

Abidović Ibrahim Rašid

Abidović Ragib Šaban

Abidović Rasim Šaban

Ademović Abdurahman Salih

Ademović Abid Ramo

Ademović Abid Šećan

Ademović Adem Bekto

Ademović Adem Osmo

Ademović Adem Zulfo

Ademović Adnan Avdo

Ademović Ahmet Sarija

Ademović Alija Halil

Ademović Asim Taib

Ademović Avdija Šerif

Ademović Avdo Nurija

Ademović Avdo Nurija

Ademović Avdo Ševko

Ademović Avdo Taib

Ademović Azem Bećir

Ademović Azmir Azem

Ademović Bahrudin Behaija

Ademović Bajro Hamid

Ademović Bajro Idriz

Ademović Bajro Osmo

Ademović Bajro Ševko

Ademović Bego Ibrahim

Ademović Behaija Huso

Ademović Bekto Omer

Ademović Bešir Bećir

Ademović Ðemo Džemal

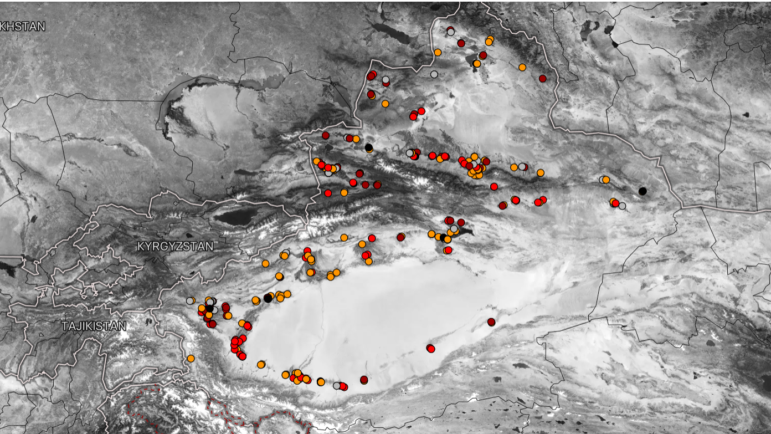

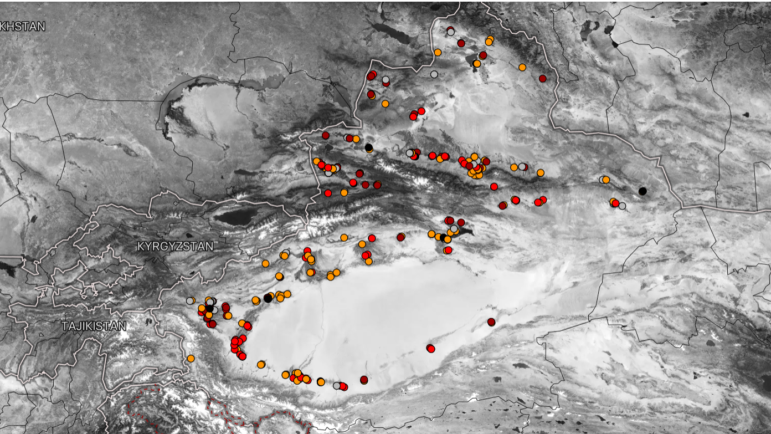

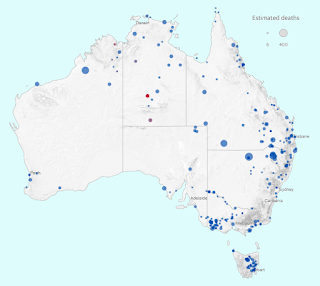

a body; many bodies, of people, let us give them some life; pick a name.

you get a name! you get a name! noone got a n̷̠̪̜̭̈ẫ̴̡̮̯͖̌̓̑̐̒̕ͅṁ̷̭̀̄͋̄̆̅̌̑́̿͛̚͘͠e̷̼͊̎͐́̽͊̑̅̌̈́̚͝.

we are people. our blood; inside. bodies are no longer people; blood outside, dried;

no chance? DYI at home shoot some kids; in a school near you.

fences kept us apart. maybe love will make us stronger;

can they walk through us? walk over us they will

the house of we grew up in crumbles;

you aren’t living, yet you aren’t there. you don't have conscience. you don’t understand

you live behind a wall of censorship you are isolated. kept inside;

tear the walls that keep us apart. only you have that power.

go through the school. pass the bodies. leave them behind. you have to go through.

the color of the body

these same bodies grounded, scattered like last rocks.

pure white bones that are born knees that fell apart grew up in house without a voice

how do you go through life? pass the knowledge with your voice.

the voice a voice but there are fake voices we need find the real voice.

use your voice where’s the voice you say you have? help them.

we are people. our blood; inside. bodies are no longer people; blood outside, dried;

no chance? DYI at home shoot some kids; in a school near you.

fences kept us apart. maybe love will make us stronger;

can they walk through us? walk over us they will

the house of we grew up in crumbles;

you aren’t living, yet you aren’t there. you don't have conscience. you don’t understand

you live behind a wall of censorship you are isolated. kept inside;

tear the walls that keep us apart. only you have that power.

go through the school. pass the bodies. leave them behind. you have to go through.

the color of the body

these same bodies grounded, scattered like last rocks.

pure white bones that are born knees that fell apart grew up in house without a voice

how do you go through life? pass the knowledge with your voice.

the voice a voice but there are fake voices we need find the real voice.

use your voice where’s the voice you say you have? help them.

The Tiananmen Square protests, known as the June Fourth Incident in China (Chinese: 六四事件; pinyin: liùsì shìjiàn), were student-led demonstrations held in Tiananmen Square, Beijing during 1989. In what is known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre (Chinese: 天安门大屠杀; pinyin: Tiān'ānmén dà túshā), troops armed with assault rifles and accompanied by tanks fired at the demonstrators and those trying to block the military's advance into Tiananmen Square. The protests started on April 15 and were forcibly suppressed on June 4 when the government declared martial law and sent the People's Liberation Army to occupy parts of central Beijing. Estimates of the death toll vary from several hundred to several thousand, with thousands more wounded.[2][3][4][5][6][7] The popular national movement inspired by the Beijing protests is sometimes called the '89 Democracy Movement (Chinese: 八九民运; pinyin: Bājiǔ mínyùn) or the Tiananmen Square Incident (Chinese: 天安门事件; pinyin: Tiān'ānmén shìjiàn). The protests were precipitated by the death of pro-reform Communist general secretary Hu Yaobang in April 1989 amid the backdrop of rapid economic development and social change in post-Mao China, reflecting anxieties among the people and political elite about the country's future. The reforms of the 1980s had led to a nascent market economy that benefited some people but seriously disadvantaged others, and the one-party political system also faced a challenge to its legitimacy. Common grievances at the time included inflation, corruption, limited preparedness of graduates for the new economy,[8] and restrictions on political participation. Although they were highly disorganized and their goals varied, the students called for greater accountability, constitutional due process, democracy, freedom of the press, and freedom of speech.[9][10] At the height of the protests, about one million people assembled in the Square.[11] As the protests developed, the authorities responded with both conciliatory and hardline tactics, exposing deep divisions within the party leadership.[12] By May, a student-led hunger strike galvanized support around the country for the demonstrators, and the protests spread to some 400 cities.[13] Among the CCP top leadership, Premier Li Peng and Party Elders Li Xiannian and Wang Zhen called for decisive action through violent suppression of the protesters, and ultimately managed to win over Paramount Leader Deng Xiaoping and President Yang Shangkun to their side.[14][15][16] On May 20, the State Council declared martial law. They mobilized as many as 300,000 troops to Beijing.[13] The troops advanced into central parts of Beijing on the city's major thoroughfares in the early morning hours of June 4, killing both demonstrators and bystanders in the process. The military operations were under the overall command of General Yang Baibing, half-brother of President Yang Shangkun.[17] The international community, human rights organizations, and political analysts condemned the Chinese government for the massacre. Western countries imposed arms embargoes on China.[18] The Chinese government made widespread arrests of protesters and their supporters, suppressed other protests around China, expelled foreign journalists, strictly controlled coverage of the events in the domestic press, strengthened the police and internal security forces, and demoted or purged officials it deemed sympathetic to the protests.[19] More broadly, the suppression ended the political reforms begun in 1986 and halted the policies of liberalization of the 1980s, which were only partly resumed after Deng Xiaoping's Southern Tour in 1992.[20][21][22] Considered a watershed event, reaction to the protests set limits on political expression in China, limits that have lasted up to the present day.[23] Remembering the protests is widely associated with questioning the legitimacy of Communist Party rule and remains one of the most sensitive and most widely censored topics in China